Tucked upstairs in the master bathroom at the Plummer House sits an unassuming but elegant marble surround fireplace. While the Dutch tile hearths at the house are aesthetic showstoppers, the little fireplace in the bathroom is interesting for a more technological reason. It appears to be a Rumford fireplace. Count Rumford (he wasn’t really a Count…more on that later) revolutionized fireplace design and from the 1790’s to the 1850’s most fireplaces built were Rumfords. Thomas Jefferson even built Rumfords at Monticello.

Count Rumford was born Benjamin Thompson in 1753 in Woburn, Mass. He was a physicist and inventor, as well as a British loyalist, who fled Boston in 1776 after he was accused of informing on the Minutemen. Back in England he applied his knowledge to the improvement of fireplaces. King George III knighted him for his essays on how to build a better fireplace. He then spent his life working for the Bavarian government, including as the Minister of War where he received his title, “Count of the Holy Roman Empire.” He took the surname Rumford from his wife’s birthplace, now Concord, NH.

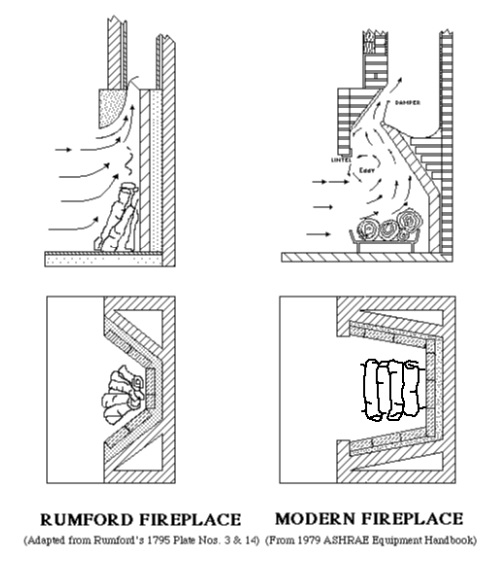

Rumford’s genius came through his understanding of fluid dynamics. Before his modifications, early American fireplaces had a lot of problems. Their wide, deep and square design wouldn’t draw air properly, heat effectively or burn efficiently. Rumford made changes to both the firebox and the chimney, creating a cleaner burning and highly efficient design that was very popular when people heated their home with fireplaces. He redesigned the firebox to be tall and narrow with a shallow depth, angled sides and a straight fireback. The shallow depth and angled sides maximized the heat reflected into the room. But tall, shallow fireplaces tend to smoke – Rumford overcame that by revolutionizing the way the smoke exited the firebox. He made the damper of the chimney narrow from front to back, which got rid of smoke at a higher rate of speed.

He also modified the “throat “with a rounded profile that streamlines air flow instead of creating turbulence. The narrow damper and rounded throat produced a strong draft without affecting the flue gasses. It let the air from the room meet the smoke as a clean sheet of air, acting as a glass door to keep the smoke behind it as they both went up the chimney. Without that mixing, the residency time of the smoke in the firebox was extended, where it contributed to radiant heating and also burned firewood more efficiently. The end result is a fireplace that radiates more heat and wastes less of the warm air in the room to carry away smoke.

Despite the popularity of Rumfords, by the 1900’s they were no longer being built. With the introduction of furnaces and radiators, fireplaces became more of an architectural element and less a functional part of the home. Masons began to give less thought to their functionality and many didn’t learn how to build a proper fireplace.

The age of the Plummer House (1857) fits with the timeline for Rumford fireplaces and it makes sense that in the otherwise unheated bathroom to have a highly efficient fireplace to warm things up.

WHALE would like to thank guest blogger Erin Burke for researching and writing this piece! If you’d like to see more of Erin’s work with historic interiors and restoration, visit her blog at www.whalingcitycottage.com.