Encased in the structure at 148 Hawthorn Street is a 110-year history of the Leander A. Plummer family. Walking from room to room, one can begin to understand how the Plummers lived. A grand staircase at the front entrance, large, ornate mirrors above the mantel, Dutch tile work adorning the fireplaces, wooden framed toilets, clawfoot tubs, and a second staircase tucked in the back of the building tell the story of a wealthy, influential New Bedford family.

The story of the Plummers, however, begins long before the house. Leander Allen Plummer was born to Mary Ann Swain and Richard C. Plummer of New Bedford in 1824 during whaling’s golden age. Over the next few decades, the population of New Bedford would balloon as it transformed from a seaside village to a modern city that would hold many opportunities for the Plummer family as its industry grew and land values increased.

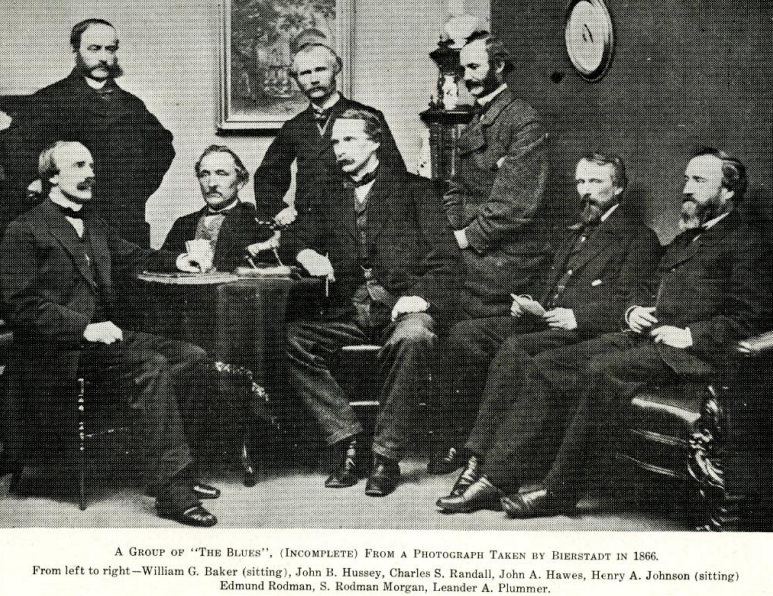

The Plummers were businessmen. At 21 years old, Leander became a clerk for the New Bedford Cordage Company. The company produced the ropes used on whaling ships, clippers, and for hoisting textile machinery as New Bedford transitioned to manufacturing textiles post 1860. In 1849, Leander married Elizabeth Sherman Merrihew, linking himself to the New Bedford elite. Elizabeth’s father, Stephen Merrihew, was the Vice President of the New Bedford Port Society, President of the Merchant’s Insurance Company, and President of the New Bedford Temperance Society. Leander moved in with the Merrihew family on Union Street, where the Plummer family began to grow until the Leander A. Plummer house was constructed in the late 1850s. During this time, Leander also helped establish “The Blues,” a social and literary organization. The organization consisted of 15 men aged 19 to 22 who had attended Friends Academy. According to an Old Dartmouth Historical sketch, these men were “of more than average distinction” and “they were fortunate youths in the incidents of birth and environment.” The group met regularly for nearly 75 years, never accepted new members, and held annual dinners and dances. Seven meetings were held at the Leander A. Plummer house and the records of the organization were passed down through the Plummer family. The group dissolved in 1905 when the last member of the group passed away.

Eleven years after his marriage, Leander was promoted to Treasurer of the New Bedford Cordage Company and fathered three children. First came Richard Clark Plummer in 1851, then Charles Warren Plummer in 1853, and Susan Reed Plummer in 1855. Stories and memories of the family after this point in time would be captured in the Plummer family homestead.

In 1856, Leander and Elizabeth purchased the land at 148 Hawthorn Street, then known as the corner of Hawthorn and Page, from Elisha Thorton Jr. for $1,850 (the equivalent of $55,620 today). Construction began at the end of the year and continued into 1857. Richard C. Plummer passed away in 1856 and would never live in the Plummer house. Susan also succumbed to croup, an upper airway infection, in 1857. It is unclear if Susan ever lived in the Plummer home or if the home was completed after her passing.

In 1857, while grieving the loss of Susan, the Plummers welcomed Leander Allen Plummer Jr. into the family. Five years later Thomas Rodman Plummer was born. He was likely named after Thomas Rodman, a member of The Blues. A year later Leander’s name appeared on the second draft in America’s history. Leander was subject to do military duty in the counties Duke, Barnstable, Nantucket, Bristol, and Plymouth during the Civil War. After the end of the war in 1865, the Leander A. Plummer family was completed when Henry Merrihew Plummer was born. As the boys grew up, the Plummer home bore witness to the troubles and celebrations of the family.

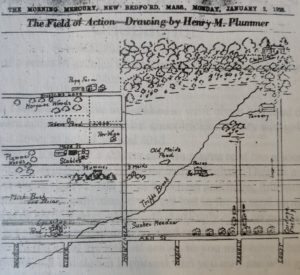

In The Morning Mercury, Henry recalls scampering along the stone wall on the corner of Hawthorn and Ash. The wall was originally located on the vast expanse of land the Plummers owned after acquiring eight neighboring lots between 1869 and 1884. At the time, the land was rural and the home faced East overlooking vast fields that yielded fruits and vegetables for the family. The boys waited in anticipation for Spring when the first ripe strawberries, radishes, and asparagus stalks would make their way to the table after a winter’s worth of apples and pears. Atlases referred to the home as “Morelands” to describe the vastness of the Plummer Homestead. The majority of the land was acquired in several transactions occurring during the five-year recession from 1873 to 1878. Labor strikes were rife as railroads and mills began cost-cutting in response to the Jay Cooke & Company bank failure. Workers supplemented their income by selling homes and boarding. For the Plummers, the recession was an opportunity to expand their wealth by acquiring the land around them for modest values ($1 to $1,295.30 or $25.55 to $27,584.28 by today’s standards). No land was purchased after 1884 when Leander passed away after living with Bright’s Disease.

Drawing of the Plummer land during the 1860s and 1870s by Henry Merrihew Plummer in The Morning Mercury. In the first of seven articles written for The Morning Mercury, Henry remembers, “In 1870, if you stood at the corner of Ash and Hawthorn Streets, looking west, you saw no houses because no houses were in sight…There was no Chancery Street, and Hawthorn Street ran out to a blind wood path, a little beyond Brigham Street. Standing again at the corner of Ash and Hawthorn, you would have looked across broad, sunken meadows”

The Plummer land was a playground for the whole neighborhood as well as the Plummer boys. As the youngest child, Henry often fell victim to the pranks of the neighborhood and used the wall as a shield from the rotting fruit thrown his way by the neighboring children. The Plummers spent hours running through the fields, racing horses, gambling marbles, sledding, using knives to sharpen arrows, create kite sticks, carve boats, and create hockey sticks before hockey was an official sport. Initials were carved into window sills and the legs of tables and chairs whittled for entertainment. Nurses, maids, and coachmen living on the premises were subject to the boys’ shenanigans. Coachman Owen O’Brien was the boys’ favorite target. One summer they handed him a branch of peppers claiming they were cherries. Owen, preoccupied with washing harnesses, popped a pepper into his mouth and yelped in pain. The children scattered in fear of Owen’s rage and, in his escape, Henry climbed over a rotting fence that snapped, resulting in a tooth through his tongue. Upset from the prank, but with compassion for the children he looked out for daily, Owen carried Henry home, his clothes bloody from the wound.

The rainy days were the few spent indoors. On those days the boys spent their time cleaning and loading guns, oiling and soaping saddles and harnesses, and preparing for the games to be played when the rain passed. When time passed slowly, they would play with a rag doll named Shedidy Jane who was always guilty of an atrocious crime. The boys would act out a court trial that always ended in Shedidy’s execution and burial in the imaginary field under the hall sofa. Fighting was forbidden in the Plummer home, but rough horseplay was common between the four boys. Henry writes “one of the most painful of which was to twitch a boy’s legs from under him at the head of the stairs and run down with a foot in either hand, bumping the victim on the hard, wooden treads,” and activity he likely fell victim to in his youth. Henry recalled feeling compassion for Thomas as Charles sent him for “an unusually painful ride” down the stairs. Henry defended Thomas by punching Charles in the eye.

The stairs were involved with as many joyful memories as painful ones. The boys spent many days sliding down the banister to the chagrin of their mother. “If you attained sufficient speed on the stretch, you could shoot over the newel post” Henry reminisced, “but if you failed in speed you fell plunk on your stomach but stayed there until breath returned.” The boys used to hold a stick in their hands and clatter them from post to post as they slid down the banister, but this activity was banned when a stick got stuck between the posts sending Thomas into the hall below with a broken arm. It was only an hour before the boys began sliding down the banister again.

In their 20s, the Plummer’s attended Harvard College (now Harvard University) in Boston. After graduating in 1881, Leander enrolled in the Academie Julian in Paris. His art classes specialized in aquatic life. The skills acquired from these classes led to a successful artistic career painting and creating relief carvings of New Bedford wildlife. The peak of Leander’s art career was in 1906 when his work was regularly exhibited at Doll and Richards Gallery in New York and he was receiving orders for upwards of 50 relief carvings per week. Leander and Thomas graduated from Harvard College before their father’s death in 1884.

1886 was an important year for the Plummer family. Charles married Mary Child Baker and Leander married Amelia Hallet Hawes, daughter of John A. Hawes, a member of “The Blues.” After the marriages, Elizabeth parceled out the Plummer land to the four boys with Thomas retaining ownership of the Plummer house. She passed away from illness soon after giving the land to her sons. A year later, Leander and Amelia welcomed their first child, Leander Allen Plummer III. Each of the boy’s (now men) families began to grow. Henry married Alice L. Hussey, his childhood love interest from Friends Academy. Leander and Amelia had a second child named Elizabeth Merrihew Plummer in 1889, followed by Anna Plummer in 1892, and Marianne Plummer in 1900. In the meantime, Henry graduated from Harvard College and fathered a son, Charles W. Plummer, in 1890. He had three other children after Charles.

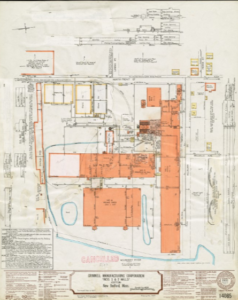

The Plummers were growing not only their families but their careers. Each year Leander was creating and selling more art. In 1892, Henry established Potomska Farm on Potomska Road in Dartmouth. It was one of the first farms to begin artificial poultry raising to mass produce poultry and eggs for retail and wholesale distribution. Henry also made a name for himself in the flour industry. In 1897, Henry bought out the Denison Plummer Company which was a combination of the New Bedford Flour Mill Company and Denison & Company (Denison Brothers). He discontinued milling of the local Eureka Flour brand and began distributing Pillsbury and Washburn flour. Meanwhile, Charles was becoming a business mogul. Although focused on the textile industry, Charles worked for various businesses. He was the President and Treasurer of Clark’s Cove Guano Co., Treasurer of White Oak River Co., and Director of National Bank of Commerce, Pierce & Bushnell Manufacturing Co., Oneko Mills, New Bedford Gas & Edison Light Co., Grinnell Manufacturing Co., New Bedford Manufacturing Co., New Bedford Cordage Co., and Howland Mill. In 1895, Thomas decided to study fine arts in France and sold the Plummer homestead to Leander. Leander moved into the house with his wife and three children (Marianne would join the family five years later).

Charles passed away in 1906 without fathering any children. Leander followed several years later, passing away in 1914 from nephritis. At the time of Leander’s death, World War I began shaking the foundations of the nation. Thomas, too old to fight in the war, sailed to Paris to pay off his debts to Mr. John Gardner Coolidge for free education at the National School of Fine Arts by aiding his wife with the Red Cross. Charles, son of Henry and Alice, also joined the war effort, rising to the status of lieutenant in three years. He died in action in 1918 while fighting with the 28th Aero Squadron. He was awarded the French Cruix De Guerre and the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross for his service. During the war, Thomas operated an aid station in the Champagne region that served over 158,000 hot drinks to the troops. He then moved to Moyenmoutier and set up another aid station in Lorraine. There he managed the village’s Franco-American Canteen for the Red Cross. Thomas grew bitter of the war. In a letter to his friend dated October 4, a month after receiving the news of his nephew’s death, he wrote “But as I am writing this, I hear the sound of German shells whistling over-head…on their errand of seemingly useless death…it drives me mad with hatred of those who begun this war for their own pride and glory and are continuing it for the same reasons.” Just a few weeks after the Armistice, Thomas died of an infection. In recognition of his brother and son, Henry Plummer named the bridge constructed over Little River in South Dartmouth the Plummer Memorial Bridge. A plaque at the bridge commemorates the services of Thomas and Charles during WWI.

Henry, the last living child of Leander and Elizabeth, wrote a series of seven articles in 1928 for The Morning Mercury detailing his childhood in the 1860s and 1870s. Soon after publishing the articles he passed away. The next death in the Plummer family would not come until 1941 when Amelia passed away. Amelia left the Plummer homestead to her oldest living child Elizabeth. Leander III had passed away in 1924. At the time Elizabeth was married to Francis Grinell and living in another home with him and their children. Elizabeth sold the homestead to Anna the following year. Anna and Marianne remained unmarried and lived in the house together until 1966 when they sold it to William J. Finn and Anne C. Finn. Two years later the home was sold again to Charles R. Porter and Eugenia Porter.

In 2018, WHALE was appointed the receiver of the Plummer home. The home had laid vacant for years. The woodwork was covered in mold and nicotine. Windows were broken and the roof had holes. The historic home had fallen into disrepair. Despite the damage, the history of the Plummer family is still apparent in this home. The grand staircase that the Plummer boys slid down still stands in the front hall. Intricate Dutch tile work from the 1870s still lines the fireplaces. Artwork from Leander Jr. is still visible on a doorway and mantle. The original entryway from when the house faced East still stands on the side of the home. Plumbing in wooden boxes, a luxury for its time, is still installed in the third floor bathroom. Perhaps the most telling mark of the Plummers, however, are the initials painted on the gable in the back corner of the third floor. It is unclear who these initials belong to or when they were written, but research on the family makes a few guesses possible. It is believed that L.A.P. Jr. refers to Leander Allen Plummer III who was often referred to as Leander Allen Plummer Jr. in census data. E.M.P may be Elizabeth Merrihew Plummer, the daughter of Leander Plummer and Amelia Plummer. A.P. may be Anna Plummer. However, if this is the case, why is there no evidence of initials for Marianne Plummer? Alternatively, L.A.P. Jr. may be the initials of Leander Allen Plummer Jr. E.M.P could be Elizabeth (Sherman) Merrihew Plummer, daughter of Stephen and Susan Merrihew. A.P. could refer to Leander Plummer who could have gone by Allen after his son was born, but this seems unlikely. This scenario also begs the question: why are the initials of Henry, Charles, and Thomas absent? It is believed that the initials R.G. could belong to Robert Grinell, the son of Elizabeth Merrihew Plummer and Francis Grinell. These initials would have been added later than L.A.P. Jr., E.M.P., and A.P. It is possible that little Robert saw the initials of his aunts and uncle while exploring the home and added his initials to the list. No answers were found for the initials W.B. or the illegible initials at the bottom of the list.

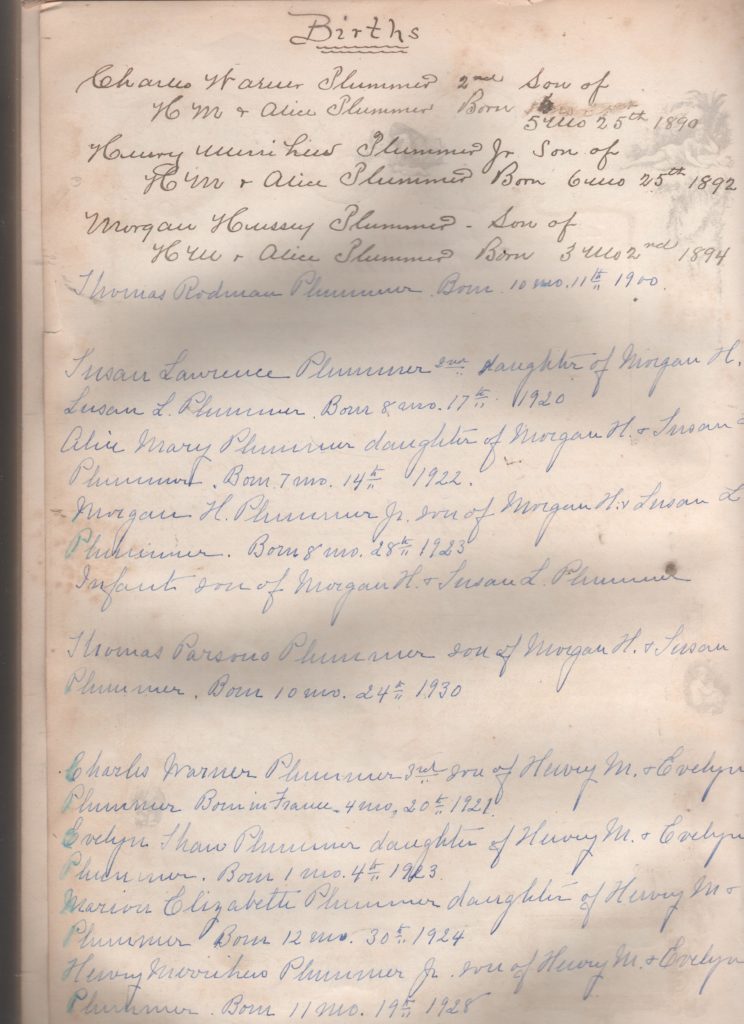

Page from the Plummer family bible documenting births in the 1800s

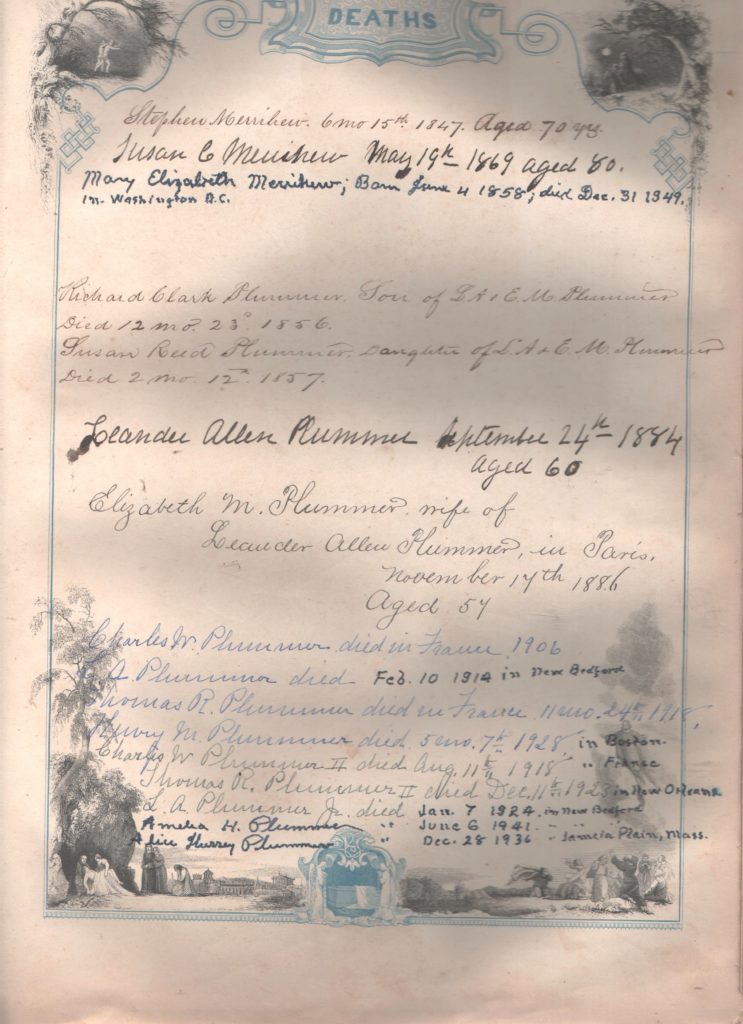

Page from the Plummer family bible documenting family deaths

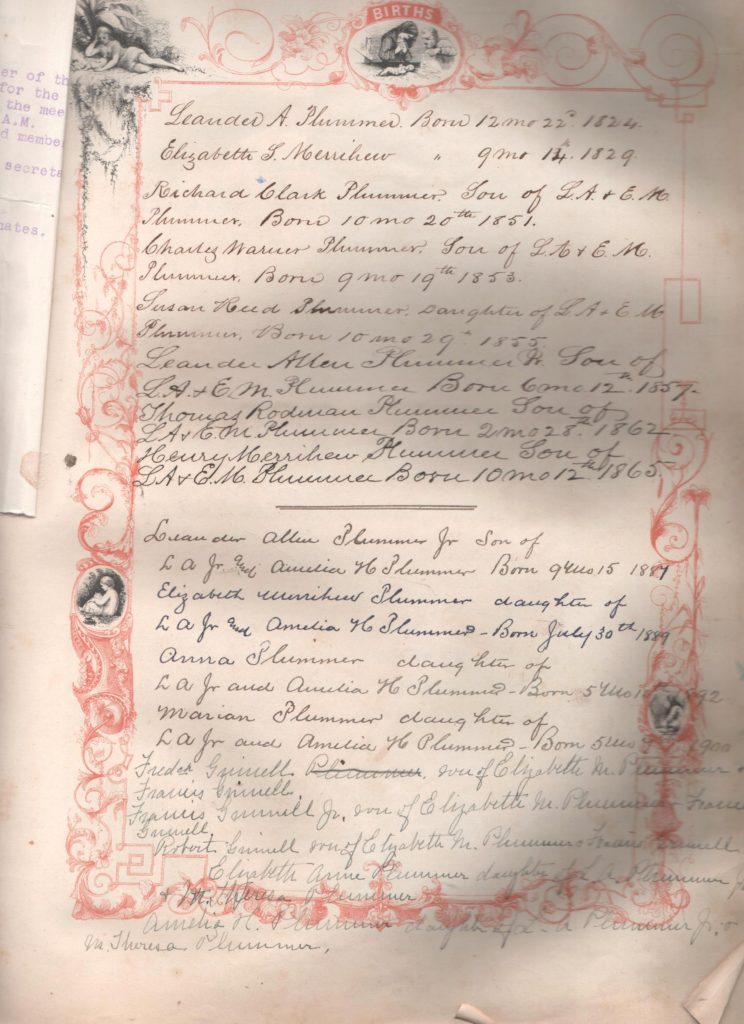

Page from the Plummer family bible documenting births

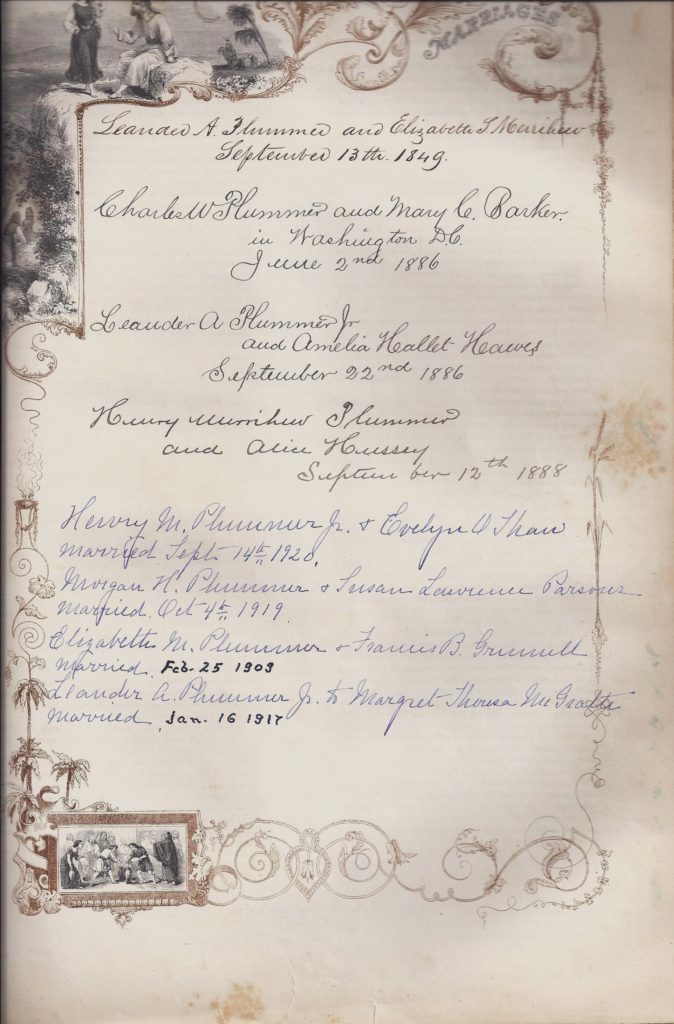

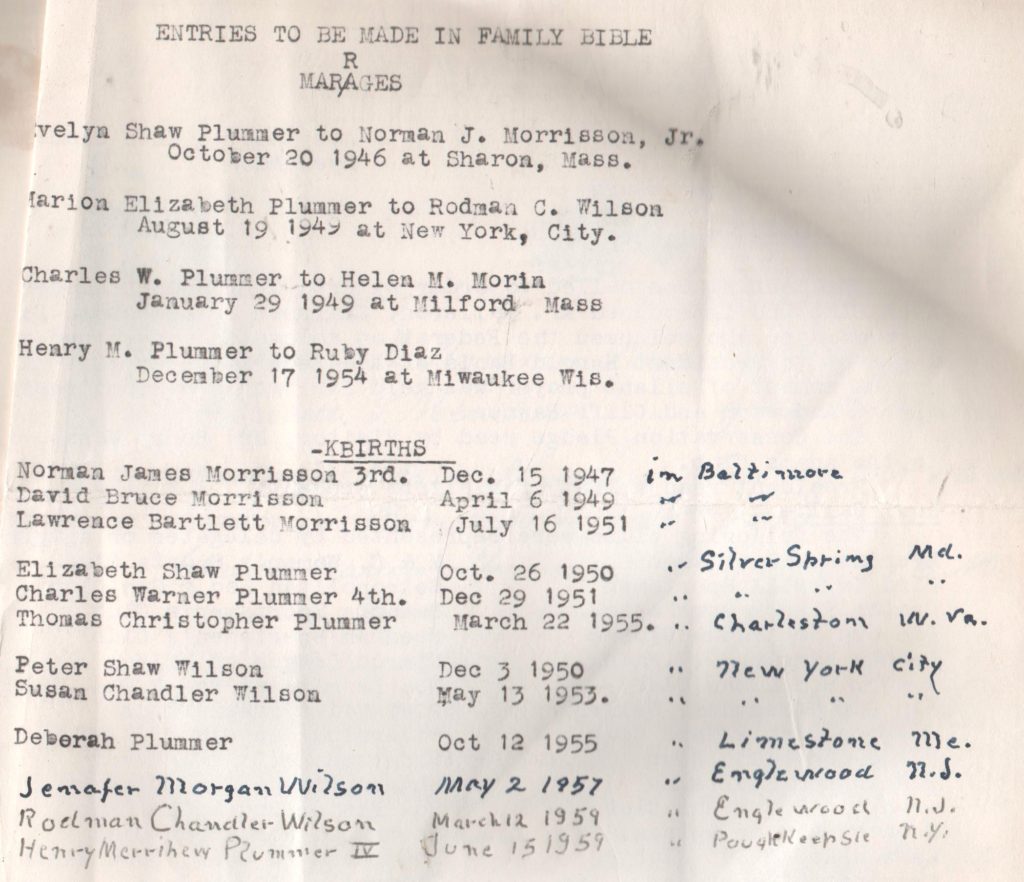

Page from the Plummer family bible documenting family marraiges

Page from the Plummer family bible documenting births in the 1900s

The Plummer house has taught us much about the Plummer family, but there are still many unanswered questions to go along with that we have learned. Rehabilitation of this home restores the Plummer story and may turn up new details of this historically wealthy and influential New Bedford family.

WHALE would like to thank John Whalen and his family for preserving and sharing the Plummer family bible. John’s careful documentation of the Plummer family made much of this research possible.